Feelings aren’t facts.

A basic principle of every non-pharmaceutical treatment for depression and anxiety involves putting some distance between oneself and one’s emotions. Psychodynamic therapy, mindfulness, meditation and exercise, to name a few, create space between us and what is running through our head. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), one of the most widely studied interventions, teaches patients to identify and challenge faulty habitual thinking patterns known as cognitive distortions such as all-or-nothing thinking and emotional reasoning. CBT entails learning that thoughts are not always a reflection of reality. Just because you feel a certain way does not necessarily make it true. Put simply: Feelings are real but they might not be true. This is not gaslighting. This is psychology 101.

Our beliefs, and the feelings that they give rise to, impact how we interpret a situation as well as our subsequent behavior. Imagine passing someone in the hallway who doesn’t say hello. You might assume that they dislike you and this hurts your feelings. As a result, you decide the person is unfriendly and avoid future interactions with them. You ask yourself, “Why bother making an effort with someone like that?” You might even tell yourself that the person is toxic and undeserving of your good will.

What else could be going on here?

Maybe the hallway snubber has a deadline to meet. Maybe they were up late last night with a sick child. Maybe they just didn’t sleep well. CBT teaches patients to consider other possibilities—indeed it may be that the person dislikes you but there are other explanations as well.

“There is nothing either good or bad, but thinking makes it so.”

William Shakespeare

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT), a close cousin of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, offers some useful data driven strategies to detangle yourself from your thoughts and feelings. Most of the time, we live in a state of cognitive fusion—fully believing our thoughts and feelings without giving a second thought. Put simply, our reality is fused with our emotions. These “defusion exercises,” as they are known, create some space and perspective.

Here are 6 examples:

The running sushi

Picture your thoughts as the many small plates on a conveyor belt in a sushi restaurant. All the dishes pass by one after another, the same way your thoughts appear and go away one after another. You can choose to reach for the plates of sushi (thoughts) or let them pass by. If they reappear later, you still don’t have to grab them.

The fish hook

Thoughts are like fish hooks, and you are a fish swimming around in the water. You can’t control how many fish hooks you come by, but you can decide whether you swim past them or take the bait. It is impossible to avoid some thoughts as you go through life, and sometimes, you will take the bait. But you can still choose to unhook yourself and swim past the hooks.

Clouds in the sky

Thoughts are like clouds in the sky. They come and go, and there is nothing you can do to influence them. Trying to push them away or worry about them is not necessary or helpful. The best thing is to let clouds occupy their own space and allow them to float by. Try doing the same thing to your negative thoughts and feelings.

Passengers on the bus

Imagine yourself driving a bus. Treat difficult thoughts as rowdy/annoying passengers. See if you can keep driving, rather than stopping when they want or trying to kick them off. Can you stay focused on driving your bus safely to your destination?

Thought train

Imagine your anxious thoughts are like trains arriving at a railway station. Rather than climbing on board, stay on the platform, and watch the trains go by.

Watch yourself

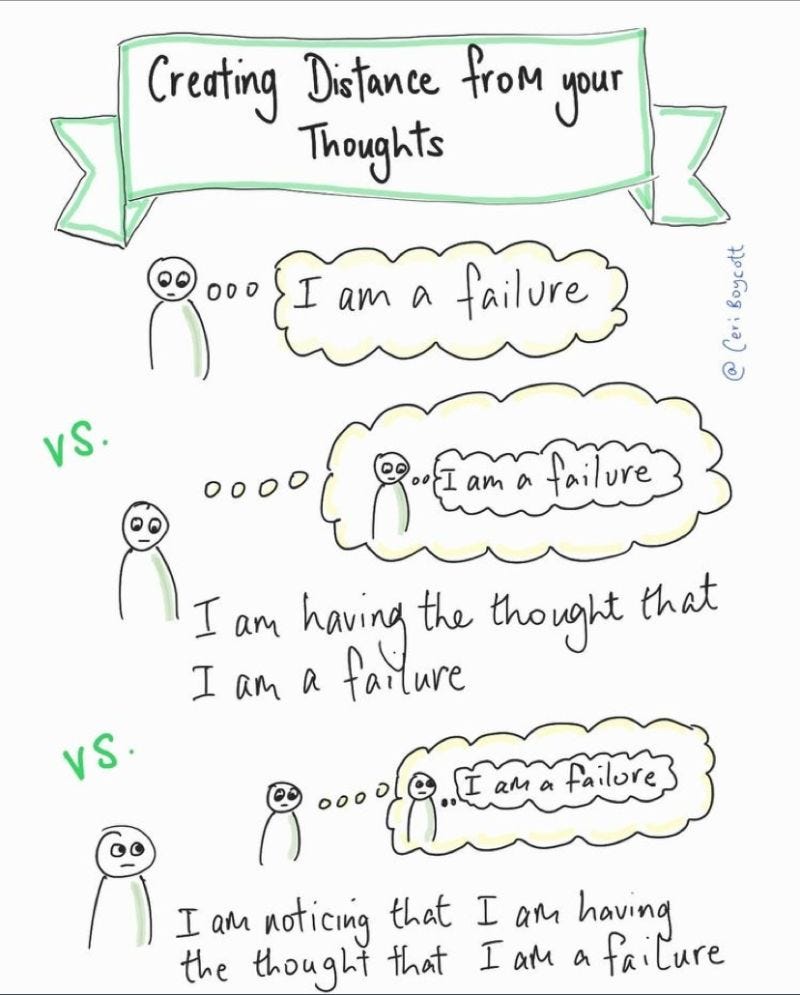

To defuse a negative thought such as “I am a failure,” say instead, “I’m having the thought that I am a failure.” To defuse it even more, add, “I notice I am having the thought that I am a failure.” I think of this exercise as the equivalent of putting on goggles when swimming in the sea. The result is less blur and more clarity.

(examples via Metacognitive Therapy Central)

We all have a tendency to over identify with our thoughts and our feelings. The purpose of these exercises is to disrupt the overthinking spiral.

One last strategy involves trading an “i” for an “a.” Writer Elizabeth Musser explains:

“Thinking too much just brings it back to me, me, me—but thanking takes my eyes off myself and my mistakes and puts them on others, on things bigger than myself. I can’t stand here very long without being humbled at how small I am and amazed at how big and beautiful our world is.”

Excellent post with superior graphics to cement the message in our brains. Thank you for sharing.

Amazing clarity. Simple and enlightening. Good analogies to drive home the single point that we don't have to stop negative thoughts from coming or going.